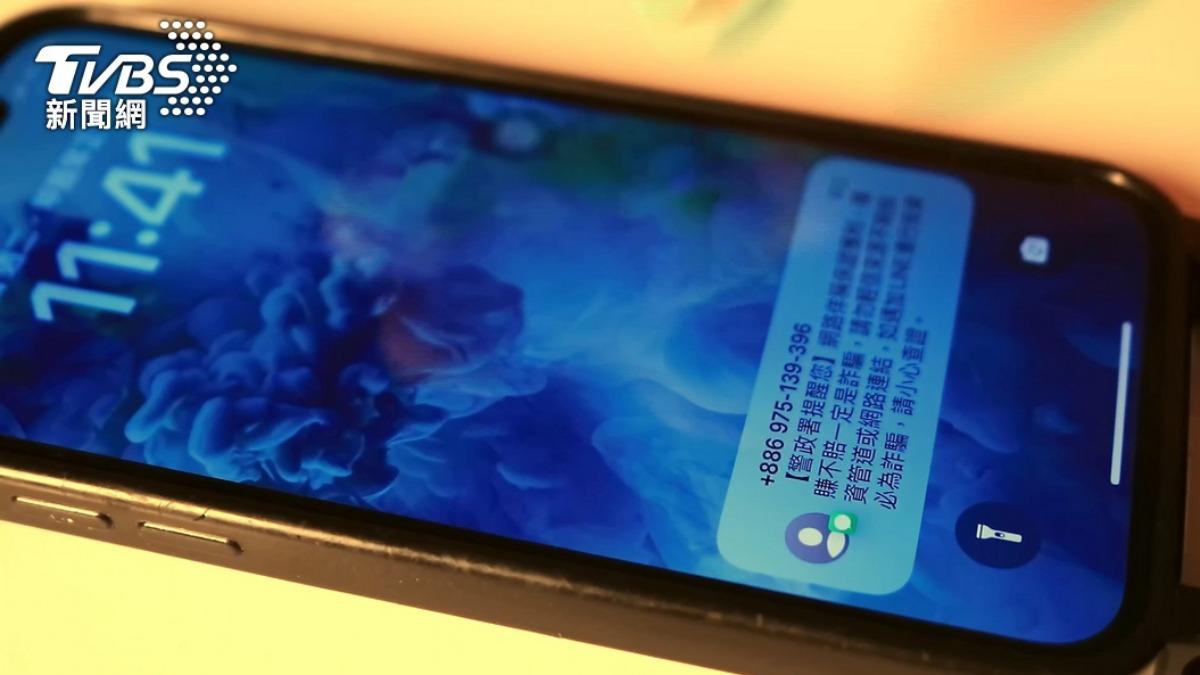

TAIPEI (Business Today/TVBS News) — In late May, Wang Yi-chuan (王義川), director of the Democratic Progressive Party's (DPP, 民進黨) Policy Committee, caused a stir with comments about using telecom signaling to analyze the composition of Bluebird Movement crowds. Scholars argue that Taiwan's outdated Personal Data Protection Act (個人資料保護法) and the lack of transparency in how telecom companies use personal data are endangering citizens' data autonomy. Are the smartphones we carry daily secretly leaking our personal data and movements?

Wang, the DPP's policy director, disclosed on a political talk show on May 27 that mobile phone location signals could be used to analyze the attributes of protest crowds at the Legislative Yuan, causing public outrage. The possibility of the ruling party's core figures having access to citizens' movement locations, ages, and other data, led to widespread fears of state "digital surveillance."

After the incident, Chen Yaw-shyang (陳耀祥), chairman of the National Communications Commission (NCC, 國家通訊傳播委員會), and Kuo Shui-yi (郭水義), chairman of Chunghwa Telecom (中華電信), attended a legislative inquiry, asserting that they had not illegally used user data and would not provide crowd analysis data to any political party. Taiwan Mobile (台灣大哥大) and Far EasTone Telecommunications (FET, 遠傳電信) also stated that their use of user data adheres to legal standards.

Tracking, Browsing History, and More — Telecoms Selling User Data for Years

Wang's comments not only didn't clear up doubts but also raised more questions. What exactly does the "legal use" claimed by the three major telecom companies encompass? How are citizens' telecom data collected, processed, and shared with external parties?

Local governments have bought mobile signaling analysis from telecom companies for large events like Christmasland in New Taipei City (新北耶誕城) and the Taiwan Lantern Festival (台灣燈會) to manage crowds and plan tourism economies. The Ministry of the Interior (內政部) also uses telecom signaling to track the actual population in various counties and cities.

Beyond government agencies, the three major telecom companies have also partnered with advertising and public opinion analysis firms, offering telecom data for targeted marketing. Chou Kuan-ru (周冠汝), deputy secretary-general of the Taiwan Association for Human Rights (台灣人權促進會), noted that Chunghwa Telecom's "CLICKFORCE" (域動行銷) and Taiwan Mobile's (台灣大哥大) advertising brand "TAmedia" (TA媒體) specialize in tracking users' offline locations, app downloads, browsing history, and daily consumption behaviors. As the data economy flourishes, using user data for industry analysis and marketing has become common.

However, it is important to highlight that whether telecom companies provide analytical data to the government or businesses, they must do so under the crucial condition that user data is "de-identified."

In the case of Wang, the three major telecom companies claimed they did not illegally provide user data because the crowd analysis data shared with third parties had removed users' names, ID numbers, and other identifiable information. This de-identified data is not classified as "personal data." Therefore, it is not restricted by the Personal Data Protection Act.

In simple terms, telecom companies can comprehensively track where citizens go with their phones, which apps they use, what websites they visit, and what products they order. As long as telecom operators remove user identity information, they can share user data with third parties at any time.

But can this "de-identified" data truly not be traced back to individuals? Do citizens have no right to object to their data being sold and used? Experts have raised serious concerns about how telecom companies interpret and use personal data.

To begin with, let's look at how the Personal Data Protection Act defines personal data. Article 2 specifies that "any other information that may be used to directly or indirectly identify a natural person," is considered personal data. The extensive use of de-identified data analysis by telecom companies may be crossing this boundary, though this remains to be examined.

Liu Hung-en (劉宏恩), an associate professor at National Chengchi University's College of Law (政治大學法律學院), noted that telecom companies currently deem data "de-identified" when they erase names, ID numbers, and phone identifiers before sharing it with third parties. Yet, if these companies retain the key to reconnect the data to the real-name database, it can still be traced back to individuals and should objectively be regarded as "indirect personal data."

In contrast, the European Union's (EU) General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR, 一般資料保護規則) explicitly requires that anonymized data be entirely unlinked from personal information, making it unidentifiable. In this regard, Taiwan's Personal Data Protection Act is considerably behind international standards.

The current reference for "de-identification" largely stems from Article 17 of the Enforcement Rules of the Personal Data Protection Act (個資法施行細則), which states that "the personal data replaced with codes, deleted data subject's name, partially concealed, or processed via other means to the extent that the data subject may not be directly identified."

Nevertheless, Wu Chuan-feng (吳全峰), director of the Information Law Center (資訊法中心) at the Institutum Iurisprudentiae Academia Sinica (中央研究院法律學研究所), candidly remarked that many companies mistakenly believe that merely hiding this data achieves "de-identification." He called on companies to understand that if the final outcome can still indirectly identify individuals, it does not meet the true legal definition of "de-identification."

In reality, to perfect the de-identification verification mechanism, reliance on an impartial personal data regulatory body is inevitable. Last year, the amendment of the Personal Data Protection Act led to the establishment of a preparatory office for the "Personal Data Protection Commission" (個資保護委員會), legally addressing the long-standing issue of fragmented personal data governance across various sectoral regulators. Yet, Wu feels that the preparatory office's current role remains unclear and that it needs to be more proactive in developing cross-departmental personal data policies.

For instance, in the telecom industry, if the Personal Data Protection Commission cannot operate at the same level as the NCC, it will find it difficult to participate in the formulation of telecom-related personal data policies, thereby failing to function as an independent regulatory body. Whether the commission will be endowed with adequate authority and resources in the future remains to be observed.

Telecoms' Data Use Lacks Transparency, Needs Prior Notice and Opt-Out Options

In addition to the Personal Data Protection Act and the regulatory oversight issues, the three major telecom companies have merely brushed off their use of user data with the phrase "legal use," leaving the public puzzled and stifling further discourse. Chou has urged telecom companies to clarify the purposes and methods of data collection, enabling deeper examination of their legal justifications.

Liu also highlighted that telecom companies are obligated to inform users and secure their consent before selling anonymized user data. Yet, under the existing standardized contracts for telecom services, users are deprived of autonomy over their data if they want to access telecom services.

Reporters thus conducted field visits to the three major telecom stores and acquired mobile broadband service application forms. They discovered that Taiwan Mobile and Far EasTone Telecommunications merely included a statement saying "informed of personal data notice," with no option to consent or decline. Chunghwa Telecom staff specifically stressed that users can opt out of receiving third-party marketing information but cannot refuse the company's use of their data.

Furthermore, Taiwan Mobile and Far EasTone Telecommunications have personal data notices displayed at their counters, while Chunghwa Telecom posts these notices online. The notices explain that data collection aims include marketing, advertising, business management, statistical surveys, and research analysis. Wu bluntly stated that these purposes are inadequately explained, leaving the public unaware of their true implications. He believes that consent should be obtained for different data collection purposes rather than being bundled into a single contract for blanket acceptance.

Teng Wei-chung (鄧惟中), director of the Consumers' Foundation, Chinese Taipei (CFC, 消費者文教基金會) and a former NCC commissioner from 2018 to 2022, acknowledged that many people eager to acquire telecom services, do not scrutinize contract details. Liu concurred, stating that this is an issue faced worldwide. Nonetheless, in the EU and some U.S. states, users can easily withdraw consent even after initially agreeing. This is a direction Taiwan's telecom industry should adopt in the future.

Wang's contentious statements have struck a sensitive chord related to "state surveillance," attracting significant attention and skepticism. The government and legislators should seize this opportunity to reassess the Personal Data Protection Act and its regulatory inadequacies. Enhancing citizens' data autonomy and refining data governance is crucial to prevent the misuse of telecom data by companies and third parties.

Here is the link to the original story on Business Today Website: 人流分析疑洩個資 民眾憂遭「數位監控」 電信業賣用戶數據 個資真能去識別化?